‘Avant-hard’: conversations from a book in the pipeline about real avant-garde performance in the UK today

Nick Awde | THE X REPORT

In late 2017 or early 2018, in a pub in Stoke Newington, North London, two hours before brutalist comedians Nathan Willcock and Phil Jarvis of Consignia are to perform at Depresstival Presents… at The Others Bar up the road, they chat to Nick Awde about how maybe to forge theatre from comedy. But first…

So It Goes – John Fleming’s Blog

‘Edinburgh Fringe, Day 8: These shows are all far too good and then Consignia’

(Aug 9, 2017, 11:52am)

This is one show which should create a sense of nervous anticipation in any audience and where Malcolm Hardee’s intro “Could be good; could be shit” resonates. And, in the case of Consignia, he might have added: “Good and shit could be the same thing here. Fuck it.”

This is the traditional spirit of the Edinburgh Fringe.

I had very little (possibly no) idea what was going on during the show but neo-Dadaism might be the best description. I was dragged out of the audience, a pink tutu put on my head to represent a bride’s veil and I was told to wave my hand while repetitive music played for I guess around 4-7 minutes. Might have been 47 minutes. Meanwhile, Nathan Willcock stood with (what I think was) a fake TV screen on his upper body and Mark Dean Quinn repeatedly hit Phil Jarvis in the face with a mop while he (Phil) yelled out “No!”.

Eventually, in its repetitiveness, this became quite reassuringly mesmerising and I felt sadly empty when it ended.

I think Stockholm Syndrome may have kicked in.

Either that or my green tea was spiked with some hallucinogenic substance.

Nothing unusual there.

This is Edinburgh in August.

(https://thejohnfleming.wordpress.com/page/43/?app-download=ios)

Just Giving – Nathan Willcock

(Aug 2017)

Weʼre raising £35 to Help Consignia to pay for an advert on mumbletheatre.net so they will come and review our Edinburgh Fringe show.

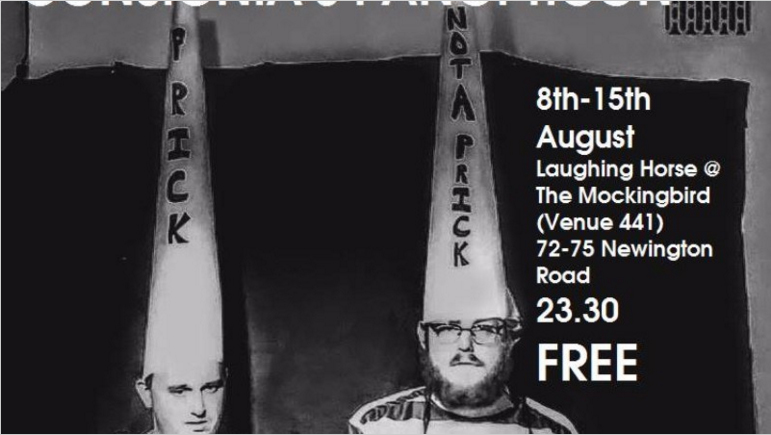

We are Consignia, a experimental ‘Dream’ Group. (We don’t perform sketches, they’re dreams.) This year we are talking an absurdist play up to the Edinburgh Fringe. It’s called Consignia’s Panopticon and it’s based on the idea of the Panopticon, a prison designed by philosopher and social theorist Jeremy Bentham. In the play we bravely ask the question, 20 years on from New Labour’s 1997 election victory, ‘What would have happened if New Labour had been a Maoist collective who sought to harness the power of atoms to enslave the population and elevate all life on Earth to a higher state of consciousnesses?’ The show tells the story of two inmates trapped in one of New Labour’s Panopticons and their brave fight against the oppressive and dictatorial ‘Floating Atoms’. It promises to be a bat-shit crazy, unique theatrical experience and an unforgettable show in the true spirit of the Fringe.

However, there is one problem. No one wants to review our show, it’s on at an awkward time in an awkward venue, but then earlier today, a small chink of hope appeared, mumbletheatre.net replied to us saying they “can only guarantee a review to advertisers – it’s £35 now, and you also get a preview-interview”.

What an offer! Unfortunately we can not afford £35. So we are humbly ask you, Earth’s population, to donate to make the dream of getting to see what some student thinks of our show a reality.

Thank you.

£0 raised of £35 target by 0 supporters

(https://www.justgiving.com/crowdfunding/consignia-mumble-quest)

Nick Awde: This will go into the book that I’m forever doing on the avant-garde or ‘avant-hard’ or ‘#shitwave’, whatever we’re calling it. It’s basically designed to be an introduction to people like you who, as I’m always saying, if you were all based in Europe, you’d be paid shitloads of money to do a couple of performances a year. You’d also be unapproachable wankers.

Nathan Willcock & Phil Jarvis: [laugh heartily in recognition]

Nick: Avant-garde today in the UK demonstrates a wide range of genre cross-over, as you’d expect, but what particularly characterises your ‘circuit’ is a generosity to other performers, regardless of ego and stuff like that, and the fact that you create shows that not only connect with their audience but also respect them. Which might seem obvious but I’ve not seen a lot of any of that in the theatre or comedy world – while conversely it helps explain why you occupy a funding-free zone. And in your particular case, i.e. Consignia, even though you are anti-everything – and brutalist – that attitude makes you come round full circle to give your shows an artistic depth and credibility. However, first tell me about the MAs you’re both embarking on.

Phil: I’ve already started deadlines and stuff on mine. I’m doing libraries and information management.

Nick: And you?

Nathan: Erm, I’m doing political communication.

Phil: So he’s the next Alistair Campbell. Mine’s distance learning.

Nick: And then what did you do as a first degree?

Phil: History and politics.

Nick: Where?

Phil: Reading. I have done a previous MA, about ten years ago in politics at York as well, but I just couldn’t get any jobs out of it. So it was just like libraries became my thing. With libraries, if you go to the public side, you’re not even called a librarian. So to become an actual librarian, you have to do these courses, like these MAs, and then you can apply to the university libraries and then become an official librarian. [laughs at the thought]

Nick: An ‘official librarian’. So just to become an official academic stacker, you’ve got to—

Phil: —you’ve actually got to go through the hoops.

Nick: So six months in Asda won’t…?

Phil: Not any more.

Nick: Right, okay. [to Nathan] And then what did you do at university the first time?

Nathan: I did history and politics as well, in Norwich, UEA. And… what’s so funny?

Nick: [laughing] It’s a pattern.

Nathan: I know.

Phil: Yeah.

Nathan: Erm…

Phil: It’s probably why, yeah, we get each other’s references.

Nathan: Yeah. That’s what Panopticon was about.

Phil: Yeah.

Nick: [to Phil] Where were you raised?

Phil: Basingstoke. So I lived, all in all, 28 years in Basingstoke.

Nick: Why Basingstoke?

Phil: My dad was a pilot for British Airways, so 45 minutes to Heathrow was why we stayed in Basingstoke. And then my parents divorced. My [German] mum wanted to stay in the area but we had the option to go back to Berlin or something like that but she didn’t want me to have that. I was about ten years old and she didn’t want me to face that situation where you’ve got to take on another language. It would have been fine, I reckon, in hindsight, but she thought that would be a bit harsh for me. So due to her being very nice, she decided to stay in Basingstoke, and then yeah, we just stayed there.

Nick: [to Nathan] And you were raised where?

Nathan: I grew up in Kent, near Canterbury.

Nick: What’s it called?

Nathan: The village I grew up in was called Dunkirk.

Nick: [laughs]

Phil: Wow.

Nathan: Yeah. Er…

Nick: That’s why you’re saying ‘near Canterbury’?

Nathan: Yeah. And the reason we were there is because my dad used to work as a hotel manager, for [hotel group] Trusthouse Forte.

Nick: Yeah.

Nathan: Which basically meant, you know, he would go wherever to manage the hotel.

Nick: And move the family to the same place, of course.

Nathan: Yeah. My sister was born in Worcester, I think, and my brother was born in Grantham. And then when I came along I was born in Canterbury. But then my dad got made redundant when I was about five and he worked in the Job Centre. My mum was a social worker, she was a nurse and specialised in adults with learning difficulties and stuff. She worked for Kent County Council, for a long time. They’re both retired now.

Phil: A lot of my mates’ mums are social workers. It’s another pattern.

Nick: And is the MA full time or part time?

Nathan: It’s full time. We’ll see how it goes. I’m going to try and balance it with my job because obviously my job is, erm…

Nick: And what’s the job?

Nathan: Media monitor. Which is basically companies pay my company to go through the newspapers as they come in. Whenever they’re mentioned in an article, you write a summary then pop them in to it. It’s one week on, one week off, because I work nights. So I’m going to work tonight ten thirty to half six, roughly. I get the days free so I can go to the lectures and then hopefully on my weeks off, that’s when I really work because I get seven days off completely.

Nick: I was going to say ‘…that’s when you really sleep’.

Nathan: No, I mean, I’ve had about four hours sleep today.

Phil: You never got used to losing that sleep.

Nathan: Yeah. It’s terrible. That’s why it was so good in Edinburgh, like doing my standup show at midday and then Consignia at midnight as well.

Phil: Turning up five minutes late during the show.

Nick: So how did both of you get into… comedy? Or what are we going to call it?

Nathan: Well I’m a standup, a normal standup, a fairly conventional, boring, unexciting standup.

Phil: And I come from a spoken word background, so like poetry and stuff. And then er, we just, yeah, I mean…

Nathan: There’s [comedian] Andy Barr who introduced me to you.

Phil: Since I first met Andy he still has this element where he has poetry in his stuff as well, because I think [comedian and spoken word poet] Tim Key was a big influence on a lot of people. Definitely a big influence on me to do that avenue, and add a sort of more comedic touch to it. Before that I was in bands and stuff like that but I always wanted to do something else again. I just felt like I enjoy performing. It’s fun. It’s a nice creative activity to do. And I was just like, well, I’m not a great musician, but I think you can be more creative using words. So that’s why I did this thing called the Dead Poets Collective, very unoriginal name, but it got me to people in some in places sort of doing stuff and got to be in the Dead Poets, when we got to a pop-up art gallery and we got to create two nights there, and the second night was one of my first ever – actually, I did my first standup, it was just quite, quite normal boring, quite standup. And then the second time we created it, I did this character called Malcolm Julian Swan, and erm that was sort of more character-based. And that’s, yeah…

Nick: You’ve lost half your audience.

Phil: There’s nothing new there. That’s pretty normal, that is.

Nick: Yeah, and then?

Phil: Oh yeah. After doing those nights it was just sort of like, “Oh, well, why don’t we make this more of a thing?” So eventually me and a friend called Imogen Wright, we started running comedy nights in Basingstoke and that’s where [comedy night] That Comedy Thing gave me a platform to do stuff as well as this character comedian thing. Well I met a lot of people from the Weirdos comedy group, they were all really supportive and stuff. Adam Larter was part of them and got me a gig at his nights and stuff like that. And that’s how I met Andy and then through Andy I met Nathan – that’s how we became mates really. I can’t remember where we met. I think Nathan might’ve come to a comedy night that me and Andy and Michael Brunström did at the Etcetera. And I think from there, Nathan was like, “Yeah I don’t want to just do all this straight standup stuff, I want to try another avenue.” And so Andy and Nathan and me, we tried it from there.

Nick: So how did you both get into comedy? Was it at university?

Nathan: Just at uni. I was in a comedy band when I was a teenager, and it was sort of like half a band. So we would do like open mic nights for normal bands but also do comedy nights. Like our first gig was like a newcomer at the Whitstable comedy festival and we sort of won, we actually won the best… this competition for new acts and we won it in this pub and all our friends came to watch it, but we were only 16. So we all got kicked out of the pub because we were too young to perform. So yeah, it was like— oh, and then I started getting interested in comedy and stuff. Yeah, I just started doing it at uni.

Phil: Me and my mate Neil did this comedy thing called the Turnips, it was weird sort of comedy but sort of music. That was the first time I ever did something that was comedy and that sort of vehicle.

Nathan: Yeah. But I was just thinking, getting into Consignia stuff, I’d always been interested in the really surreal weird comedy. Like I always hear loads of comedians, who came up in the 80s or alternative comedy, talk about like this bloke who used to do it called the Iceman. Have you heard about him? He would just melt a block of ice and no one really knew much about him but he’s sort of got this mythical status in the comedy world. And I was well that’s great. And so I would like yearn to do something a bit like that. I had a few sort of weird characters, like I had this character called Mr Niche, where he goes up and just does really niche jokes that deliberately the audience won’t get. They’re written like conventional one-liners, the structure is the same. So I deliver them the same as the jokes. And then there’s a pause and then there’s normally a laugh. So I found that stuff really interesting. So I get the jokes but then no one else does. And that’s quite, quite, funny.

Phil: I find it sneaky, getting that awkward laugh.,

Nathan: Yeah. So it’s the laugh that comes in the pause. Afterwards.

Phil: Yeah.

Nathan: I used to do that whenever I got disillusioned with standup, like I’d do a gig as Mr Niche like a catharsis for when I was getting really annoyed with the standup thing. But then, I dunno, I found Phil and Andy, and realised that that’s [laughs] probably more successful than anything I’ve ever done when I do it in the right way.

Nick: Well, before we start talking then about the beginnings of Consignia and the journey that it’s quite clearly on it’s interesting, you both mentioned that, you know, you were in bands for, for a reason. I mean, not necessarily sort of getting into a band and play punk from the age of eight years old until you sign that deal when you’re eight or when you’re 18 or something like that. It’s quite, it’s quite interesting that, you know, you clearly actually enjoy the collaborative process and of having someone side by side and actually certainly in this, in Panopticon, you actually play to the audience as you would if you’re a band, not to each other most of the time.

Nathan: Yeah.

Phil: Yeah, yeah.

Nick: I mean, I mean, not to put too fine a point on it, but it’s sort of, it’s like, it’s, it’s interesting and probably quite significant then how you sort of found each other underneath, you’ve got things ticking away, but in fact, you’re sort of band members as opposed to solo members and you know, your egos are just as awful as all the rest of them but you know you’re quite happy putting them in a room together.

Nathan: Yeah. But that’s the thing though, because I’ve always been interested in doing something with other people in comedy, but there is that ego thing. I still get very annoyed if people aren’t on the same page as me, and I find it difficult to work with someone if they don’t get what I can be. If people don’t go with my idea, I’m sort of a bit like, you know, I’ll just go off in a huff. I’ll have this thing in my brain, “Well I’m clearly right and they’re wrong.” And it’s caused a bit of tension. But then when I found Phil and Andy, we all seemed… even I’ve been friends with Andy for a long time, whenever we’ve worked, done anything together, because we are quite different standups it never quite worked with just the two of us, but bringing you into the mix, I dunno, we just sort of all gelled didn’t we? I think because our cultural references are the same.

Phil: Very much.

Nathan: Our style of humour was the same.

Phil: I think that Chris Morris was always a first reference for everything. And then, erm…

Nick: Interestingly, his first wave of stuff came not from uni but from our class humour. Cause we were all in the same year at boarding school for ten years and didn’t have much else to do. Luckily he was the one who went off and used it. We were very happy because the rest of us weren’t going to do anything with it, and it was so finely tuned it would have been a waste.

Phil: Amazing.

Nick: It was honed particularly in the period when we were all in the same class in the years leading up to O-levels.

Phil: There’s that book isn’t there where it’s sort of very much, he was a bassist. Wasn’t he? in a—

Nick: For a while yeah.

Phil: And er… Yeah, I think Chris Morris is sort of someone we’d sort of like… I think there was a point where a lot of people feel Chris Morris is a big influence and yet I don’t see many people trying to really play around with what he was trying to do.

Nick: Why do you think that? [to Nathan] Do you agree with that?

Nathan: [suspiciously] What do you mean? So..?

Nick: Well—

Phil: There’s that subversive element about it.

Nathan: Yeah.

Phil: I don’t feel you get that as much in comedy – or a lot of people will say, “Oh Chris Morris blah blah blah”, but it seems like—

Nick: —they don’t do it.

Phil: They don’t do it. Yeah, yeah.

Nathan: Yeah. Cause I mean, I would say probably our stuff is more, if it comes from any sort of Chris Morris thing, then it’s even more close to something like Blue Jam.

Phil: Yeah.

Nathan: Sort of like that really—

Phil: —late night.

Nathan: Yeah. Sort of woozy, he created a world that was all a bit disturbing and—

Phil: —drunk, drugs sort of—

Nathan: Yeah.

Phil: —a blur.

Nathan: Yeah. Cos I think Blue Jam, the radio series, is like some of the best things he’s ever done, I guess. Could be because he just—

Phil: And that’s got a lot of music in it as well.

Nathan: Yeah.

Phil: Which we have that. Especially last year’s show, The Abridged Dapper 11 Hour Monochrome Dream Show. There’s a little bit of the element in that with this year’s where we’ve got the slowed down mop scene. There’s that music slowed down and that’s very Jam-esque, but last year’s show was just a constant soundtrack of music and sound. That was, it would change each gig. So the gig had sort of sound quotes from—

Nathan: —the test tube—

Phil: —politicians, Ceaucescu’s, er, last speech mixed in with just very—

Nathan: —like with UKIP calypso with—

Phil: —a lot of music that we’d like found sounds that we’ve made and then incorporated into the show.

Nathan: Also Andy made a lot of them. They were really good. And at the end of it, like he, well at the end one of them he would just belch really loudly and we wouldn’t know when it would come in the show. But wherever it came in the show, then it would completely kill the sketch we were doing, because it would just flare out like—

Phil: —it was like a Russian roulette.

Nathan: And there was the like—

Phil: —in the last part of the show—

Nathan: —he did a big explosion and gun sounds, and again that would just completely kill it. So, yeah, we deliberately built in things to the show which would sort of destroy the show and like—

Phil: —interject. And we’d interject that we have no control over it.

Nathan: We weren’t actually in control of the show really, which was cool. And then I was thinking about it. It’s probably what we sort of did that with Panopticon as well, it was interesting because we just did it at the London festival, Objectively Funny Festival, and my friends came to see it and my girlfriend came to see it as well, and their thing was like, “Oh I enjoyed the first 20 minutes and then it got a bit like weird and like I sort of lost…” That, I think, was because the first 20 minutes is quite conventional, it has setup–punchline, setup–punchline, and then the show sort of collapses in on itself doesn’t it?

Phil: I don’t know—

Nathan: Because it just gets a bit—

Phil: —I don’t think it collapses. I think it just, it becomes—

Nathan: —unwatchable—

Phil: —because I personally don’t like the—

Nathan: —mucking around—

Phil: —I don’t like the ‘Working Lunch’ bit, but everyone we’ve sort of talked to sort of goes, “Oh yeah, ‘Working Lunch’.” And I just feel—

Nathan: —I liked the hack—

Phil: I thought it was quite a hack.

Nathan: —I liked having a hack—

Phil: So I found that—

Nathan: I don’t think it’s quite that bad…

Phil: —so I find that everything after ‘Working Lunch’ I actually liked.

Nathan: Erm.

Phil: I find the show is about getting over that bit. It’s kind of like I’ll just get over this bit enough and then I can enjoy the show.

Nick: Let’s go back a bit. So what happened to Andy? Because Andy was with you—

Nathan: He is still.

Nick: —and you were a trio and it was beautifully fluid, well, at least what the two of you did with him.

Phil: Well he—

Nathan: Erm.

Nick: And you said that he been part of setting this one up, Panopticon, but—?

Phil: He had a clash of his show times [at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe 2017] and due to the whole way to get your show at the Fringe it just was a nightmare, because also you’ve got the gamble of like, am I going to get a show [slot with a venue] or not? Andy gets his show first, his offer first. So we’re kind of thinking like, “Well, Andy, we don’t even know if we’re going to get a show…” So Andy goes ahead and makes his plans for his own show, his solo thing, which is quite late at night, which is the kind of time where we occupy. I think there was a stage where we were thinking like we don’t even know if we’re going to get a show basically—

Nathan: Yeah—

Phil: —and then—

Nathan: —it was pretty much on the last day before offers, before the brochure deadline, we got offered this slot—

Nick: But it wasn’t offered you in a particularly positive way, was it?

Nathan: No. Yeah. Alex Petty [head of Laughing Horse venues] didn’t—

Nick: How was it put to you?

Phil: I think I’ve got the email somewhere. But it sort of says like, “This venue, The Mockingbird, was run by different people last year. It was…” – words to this effect, that “it was difficult last year for people to access.” Because if you look at the map of the official Fringe, it’s just at the bottom right-hand of the grid, it’s on the outskirts of where all the action is. It’s beyond it. So, you know, Alex was like, “I just want to warn you in ahead that this is—”

Nathan: —and after that, putting it on at eleven—

Phil: —“this is quite hard if you’ve going to get any audience”—

Nathan: —it was eleven thirty at night. So if it was hard during the day, then doing it at night would be impossible, nigh-on impossible. And also there’s another reason why Andy couldn’t do it. Cause he was at the Dragonfly [venue in central Edinburgh] and if we were at somewhere like Three Sisters [also in the centre] or somewhere then he could have just walked—

Phil: And that was the other thing with Andy—

Nathan: —but it looked like he wouldn’t be able to make it because it was so far away—

Phil: —because it was like at least a taxi ride about 10, 15 minutes away and—

Nathan: So yeah, that’s the only reason – and we’re hoping to work with Andy again on our other shows and stuff, but that was—

Phil: —but even now… This gig we did with Andy last week, it was really good to have him in it because it had this meta style, this sort of tension within between Andy and us, because we’ve done this piece separately to him and then brought in the [real-life] backstory of Andy having his all stuff just nicked and having this benefit gig for his lost property and stuff.

Nathan: But also because he knew us so well, he sort of tore the show apart. Like he was very much like the director as in a very abusive director to us. So he wasn’t afraid to really derail the show and make it like, it wasn’t really about the narrative, was it, it was about… it was more like one of those play within a play things? But it still sort of worked I found.

Phil: But I think you’re right in a way. I think me and Nathan feel more confident if Andy can’t do it! Because I think beforehand it was like I was thinking obviously it worked because it was me and Nathan and Andy, and then it was like, well actually it’s me and Nathan and that works too.

Nathan: Well I think that it forced us to go into a different direction without Andy, and you know it turns out that we can actually create something which is okay. Because with Panopticon we were worried. I think that if we’d gone with Andy, then there would have been the temptation to just do like another version of the first show [The Abridged Dapper 11 Hour Monochrome Dream Show] which is like a weird sort of semi sketch show. But then with Panopticon we managed to… it forced us to do something different, which is make a narrative and build—

Phil: I think, yes, like—

Nathan: —a map.

Phil: —I know why we went and did Panopticon. It was sort of the influences I wanted, I mean I did a show the year before called Kafka or Magaluf and it was meant to be like a play. But it was so sprawling that I thought I’d always felt like it was best to make it a bit more… more minimalist sort of very easy. And that was where I’d always wanted to kind of go. I felt really frustrated that at this gig that we did at Leicester [Comedy Festival] – me and Andy and a guy called Sam Schafer – no one walked out the room but it was a really weird show and it just felt like, I just didn’t feel satisfied with it and just wanted to go back to sort of a more play format. I’d watched Edward Bond’s Dea at the Sutton Theatre and it was a notorious car crash of a show. But all the way watching it, I was like, well, this is unintentionally funny, but why isn’t this style of theatre actually played in that hybrid area where it’s a comedy gig but also it’s got that threat of violence that Edward Bond, Sarah Kane has? And if you look at Sarah Kane’s sort of stuff, which Edward Bond’s clearly influenced in theatre, this sort of kind of more minimalist text. So you don’t really need to have a big sprawling play. You just need to make it sparse, write a sparse script. So the Consignia script’s about 11 pages and that’s all we need. And that lasts an hour. That’s an hour gig.

Nick: Erm, sometimes more. Which would be value for money except it’s a free show.

Nathan: An hour 45.

Phil: Yeah. So Edward Bond was a big thing. And then watching Steve Reich with Lottie and Nathan doing a minimalist set around his 80th birthday which was on at the Southbank. I was also saying to Nathan, “Is there such a thing as minimalist comedy? You know, if a comedy is inspired by that minimalism?” I mean it’s fucking pretentious, but I think there is something there, you can make your minimalist form of comedy where it’s very sparse in the dialogue and stuff and you’re thinking, well how does Pinter work? You know, a lot of that tension in the boredom, And so in a way that idea lends itself to being this ‘theatre comedy’ sort of thing.

Nick: Yeah, but it’s not really ‘comedy gig-theatre’.

Nathan: Yeah. But I think with Panopticon it is that it’s a comedy show. If you actually took it structurally… I know it’s dressed up in all these silly costumes and silly references, and also our ‘amateurness’ and our anti professionalism all mixed up, it doesn’t lend itself to the… it doesn’t make it very—

Phil: —professional—

Nathan: —professional. But the actual narrative, the story, is really, really bleak. You know, it’s about autho–, auth–, can’t speak now—

Phil: —tarianism.

Nathan: —authoritarianism. Both the main characters die, there’s no redemption for either of them. It’s set in a prison and there’s a torture scene, pretty much. So it’s a bleak show, but then it’s sort of wrapped up in our sort of stupidness and also there’s a couple of times, like in the last show, where it was weird because the bits that were getting laughs, the last show we did in Edinburgh, the bits that were getting laughs throughout the run that night didn’t get laughs. So the bleak bits people watched with almost horror, or with silence, but then there were other bits that people did laugh at—

Phil: We had to interject, we had to kind of reveal the mask, like this isn’t actually painful.

Nathan: Yeah. There’s people who were, when Phil was getting hit by the mop, getting actually distressed cause he was getting hit by a mop. And then also [comedian] Marnie Godden, who directed that one – you know, played the role of the director – she really didn’t want to feel or be violent in any way. So it was sort of, erm—

Nick: She was actually intervening in the mop scene, wasn’t she?

Nathan: Yeah.

Nick: Which was an interesting situation to observe.

Nathan: Yeah, because you were there, weren’t you?

Nick: Yeah. It was a really interesting level of – the reaction, even if unforeseen, is all in the script.

Nathan: Yeah, but then if you contrast her performance as the director to Andy’s performance, they were two completely different shows because she obviously wasn’t aware where the show was going and she didn’t want to hurt anyone and wanted to be as nice as possible. And it still sort of worked, you know, people were still laughing at that show, whereas Andy, he was aware of what’s going on and he did very much want to sort of—

Phil: He wanted to flay us.

Nathan: —humiliate us—

Phil: —yeah—

Nathan: —like really make us work hard, and that sort of worked as well. I think people enjoyed that as well.

Phil: Yeah, we had that—

Nathan: [to Nick] I think you’re probably quite good on this. Cause you saw a number of different versions, so you could see how it did also just rely on the—

Nick: Well, that randomness you were talking about with the previous offering of The Abridged Dapper 11 Hour Monochrome Dream Show and stuff like that, you just basically formalised it by having a device which introduces a whole dramatic level to the play. If someone gets given a script and they’re part of it while they may or many not know what’s going to happen – the latter mostly in Panopticon’s particular case – it really does help focus on what you’re doing in the rest of the play. Intended effects or not, you go with it all and, picking my words carefully here, you stick to the script. That’s the point.

Nathan: Yeah. And we were talking about this, weren’t we, we were like, because the last year we very much definitively killed off the previous show we were working on, like with the story of the props and it felt like a natural end, oh yeah we don’t want to do this. [After performing Abridged at Leicester, they destroyed all the props they’d made for the show so there was no temptation to do the show again.] But with this one, we feel that it could probably, we can keep it in the back pocket and like this, it can run and run because we literally just could have anyone in the director role, just hand them the script. And then the show, it’ll always feel fresh I think, because we’ll never know how it goes.

Phil: I think at the Fringe there were other shows doing that sort of thing where someone’s given a script for the first time.

Nathan: Yeah.

Phil: It’s quite an avant-garde technique, but it’s very comfortably avant-garde. I mean, it’s very—

Nick: Well when one person gets given the script in White Rabbit—

Phil: —Red Rabbit, yeah—

Nick: —or Whatever Rabbit, and the playwright has had another play up, which is called—

Phil: —’Something Else’—

Nick: —’Something Else’, which was on at the Traverse this year [during the Fringe]. And that was a similar thing. You get given the script or you get given instructions or whatever, but ultimately that’s safe because it’s just one person onstage. And there isn’t that real danger, you can’t imagine the producers wanting it to go wrong. Or the audience, sadly. They don’t want to start solving problems in real time, live. They won’t envisage it being ‘showtime!’ and thinking, fuck, you know what, it’s going to go that way or it’s going to go that way or it could go both ways at the same time. I happen to know the producer of the latest play that was on at the Traverse, and he’d get all of Panopticon, but he wouldn’t put it on at the Traverse, or anywhere comparable in London. No one would. All those gatekeepers. It’s—

Phil: —too much of a gamble—

Nick: Yeah, exactly. I mean, he would love this and he’d dive at the chance to take on the role of director or wear the tutu. But you realise even though, that with the Traverse show, even though it looks risky and avant-garde—

Phil: —there’s a safety net within it—

Nick: Yeah, there is an in-built safety net. You, on the other hand, by mixing and matching and genuinely throwing it open to the audience, it just becomes totally, genuinely new each night and—

Nathan: But then that whole show when Marnie did it, things really did go wrong. The iPad broke at the beginning and that sort of really threw it, I was worried for the whole thing.

Nick: Well that’s what I was going to say, is that you the performer can’t even predict what your reactions are going to be. Because, like Marnie’s night proved, it got personal for you, which changed everything.

Nathan: Yeah. And I felt really bad because it was sort of, I couldn’t enjoy it. In the end it was fine.

Nick: That’s the point, it was fine.

Nathan: It was. There was nothing wrong with the show, but I wasn’t able to enjoy, and yet it was such a good way to end the run in retrospect. [In reality, the final show was an intentional no-show, where the audience turned up to an empty theatre space and slot on the last advertised night] And you got quite annoyed with me cause I was in a bit of a mood and I was like—

Phil: Yeah, yeah, well.

Nick: But you weren’t half naked covered from head to toe in Vicks ointment and suffocating at the time, like Phil.

Phil: Exactly.

Nick: So I think both of you had actually put yourself into a logical last night impasse beyond which there was no, there was no going back, basically.

Phil: Yeah. At the end of the day, we got to do the show for an hour and 45 minutes to, as [comedian] Mark Dean Quinn described it, “an audience that was 30 percent hating it and 70 percent wanting to start a cult”. You know, it’s the ideal scenario really to end your last show.

Nathan: Well, after one show I spoke to someone who’s a comedian. I didn’t expect him to come along – well, I don’t really know him so he must’ve just come along because he wanted to. And he’s all sat in the front row and looked quite uncomfortable throughout the whole thing, and I asked him about it afterwards and said, “Oh, what’d you think?” And he was like, “Yeah, I mean, I enjoyed it but I was surrounded by loads of people who were laughing really heartedly. But I was streaming wet, I walked to the venue in the rain. It’s half past one. By the time it finished, I was really tired. And it’s a really hot room…” Basically he just sounded like… I think his point was that all the elements of the setup for the show just made it horrible to sit through. [laughs]

Phil: But in a way that is intentional, it’s meant to be like a Late and Live thing. It’s meant to feel like this is something you’ve sought out, something you’re signing up to. That tends to get people who get it. You’re not going to turn up at half eleven and watch something you think is going to be—

Nathan: —in the middle of nowhere—

Phil: —if you see that at half eleven, you’re either going to be like, “Well, that wasn’t as weird as I thought”, or “Yeah, that was what I wanted to see.”

Nathan: It’s called ‘Consignia’s Panopticon’, as well. When we put it in the programme, we realised that most people probably wouldn’t know what either of those words meant. [laughs] It’s like that bloke who took acid and went mad and rushed out and had to leave Edinburgh during the show – if you’re going to drop acid before any show, don’t do it particularly before that show, you know, that’s not going to—

Phil: —I mean, yeah.

Nick: So, okay. Okay. So then, so then it comes down to, so let’s talk about the wider thing, the anti-comedy, the anti-theatre, the brutalist #shitwave progression as well. As Consignia’s developed, there’s also been this progression where the more you use the word ‘anti’, the more it becomes an incredibly positive huggable sort of thing. Again, not for the person who’s just dropped acid or struggled soaking wet in a hot room, but it’s not as uncompromising as in-yer-face performance, which I’d argue is what Chris Morris is all about. A lot of his stuff can be seen as quite snide, quite arty and sort of “aren’t I clever at taking the piss out of everything”, where form deflates his satirical design—

Phil: But there is a message in Chris Morris as well—

Nick: —yeah, which is—

Nathan: —and also it’s as silly as hell, Chris Morris’s stuff is really silly. Like it’s presented in a very stern way, but it’s actually just ridiculous. Like, you know, half of Brasseye, it’s just ridiculous concepts, just really funny. Or like in The Day Today, with horses on the Underground. Some of that’s just very surreal ideas but because it’s presented in a very straight way, people think it’s, erm—

Phil: The anti-stuff… I don’t know, I mean it’s sort of, I suppose, like anti-comedy. The stuff that I put in is like when you read out, say, a council letter, a planning notification to the community, and then you know that works in this context somehow. I don’t know. We’ve made things where you can read out quite bland things but if you give it some slight kind of narrative, like pull it in within a narrative, it kind of works – or maybe not, I don’t know.

Nathan: But I think when me, Andy and Phil were setting up Consignia… I think especially for me and Andy, we wanted to set it up because of our disillusionment with the comedy industry. We were bored of doing what we were doing and we were looking for an outlet. And when we first started, the whole point of last year’s show was we set out saying that we’re going to make something that we’re going to specifically ask to be on at the Fringe at a really antisocial time, like 1:00 a.m. or something. We’re going to put it on at that time and we don’t care where the venue is, even if it’s outside of Edinburgh. All the ideas that we have, no matter how weird, we’re going to work on them and we’ll put them all in. And we want to make something that has no commercial viability whatsoever and no pretensions to that. We weren’t seeking to get anywhere with it. We were just literally… because comedy’s a very—

Phil: —and we’ve got references to like—

Nathan: —yeah, and like—

Phil: —‘Proto-Reality TV’—

Nathan: —yeah, exactly. And like, comedy’s very… obviously for most comedians it’s very driven and self-serving, and they, you know, they don’t want to—

Phil: They want to look cool.

Nathan: They want to look cool. And then they’ve all got this bigger thing in mind. And I’m as guilty of it as well. You know, you play it safe when you don’t want to upset it too much. So we just wanted to completely get away from that and just make something so weird and out there that it just opens it up like a sense of freedom, to be like we could do whatever we want. It’s actually turned out that if you do that, then people go, “Oh, this is… good?” I think people seem to like it because it’s so refreshing. And some people respond to that positively because no one’s really doing this. I remember when [comedian] Ali Brice came to see us the first time and he was a member of the Weirdos. And he actually said, “Well, you know, we called ourselves Weirdos, but that is fucking something else!” Which I was really proud of. I was like, “We’ve out-weirded the Weirdos which are like the reason for our company being set up.”

Phil: —yeah and Ali said, “I am the Weirdo of the Weirdos.” So that’s just like—

Nathan: —we had the two main—

Phil: But then I guess it’s part of that thing about access. It’s probably because I don’t live in London and I don’t have access to all this. I don’t have the contacts or network or whatever. And also I don’t have the energy to do the stuff that most of what the Weirdos do. Because a lot of them come from a drama school background and they’ve kept themselves in shape and they’d be doing all these quite high impact sort of works. If you watch Adam, he’s a teetotaller and he’s got the energy.

Nathan: [laughs]

Phil: Half the reason we’ve got seats in Panopticon is because I need a seat.

Nathan: [still laughing] What did he say? “If you print something off, it’s going to be Arial 16 cause my sight’s going!”

Phil: Yeah. It’s sort of—

Nathan: [continues laughing]

Phil: He needs to, erm…

Nathan: [still laughing]

Nick: Sorry if I’m interrupting, but there’s a strange irony in that you’re the ones who – with Andy of course – have come up with something that’s more than just theatrical. What do I mean… coming up with a real piece of theatre inadvertently through fumbling your way, knowing you’re fumbling your way – and not really giving a shit about it but actually giving a shit about it. Like you’re saying about the Chris Morris thing – it’s silly but there’s a dark seriousness underneath it. Erm, and a structure, surprisingly. So… you’ve formulated a way of theatre-making that ‘real’ theatre-makers can find references in from theorised avant-garde theatre as we’ve known it down the line. But because you’ve come from the direction you’ve come from, it can only be different.

Phil: It’s got a different spin on it. At least.

Nick: And also as you’ve just alluded to – well, in fact as you’ve just explained in detail – you do control it, and you control it because you don’t want it to be predictable. If that creates weird sort of brutalist shit for the two of you and your audience, then it makes perfect sense. Well, to me at least.

Phil: To me, hell would be to be a standup comedian who gave a shit, who had to follow some sort of a gang. I mean, I love watching Nathan as a friend but when I see Nathan do a straight gig it’s very much, like it would bore me just to go up on stage and tell you jokes like that—

Nathan: —it bores most of the audience—

Phil: —no, they enjoy it. But it’s sort of like that kind of—

Nick: I still haven’t downloaded your show, Nathan—

Phil: [laughs]

Nick: —I’ll do it tomorrow.

Phil: I prefer to do this sort of thing where you can have anti-comedy and you can have awful bits. And if people are nice enough to say that what we do is in touch with theatre, then when there’s no laughs, we’ll go, “Well it’s theatre!” [all laugh] You can always know that it’s the way out.

Nathan: But when we were writing Panopticon, we were very much like we need to play it straight as possible. We were like, “Yeah, we’ll do this, we’re going to do it, we want to do it as a piece of like in our heads. So let’s do this as straight as possible, we’ll play it straight.” And when we spoke to [comedian] Ben [Target] as well, he very much suggested that we don’t play it in a way that The Play That Goes Wrong sort of thing. Because he said that’s very difficult to pull off. So in our heads I think that every, every, every time we did it, I would have liked nothing more for it to go completely straight and nothing to go wrong, but then it just naturally does go wrong. Even just walking in with the hats [at the beginning of the play], the hats always fall off, even though that’s not intentional. We don’t necessarily want them to fall off, they just do.

Phil: I wouldn’t say it’s anti-theatre, I think it’s more like amateur theatre, isn’t it? Amateur theatre has that DIY, lo-fi thing built within it, so things will fall apart and go wrong.

Nick: Well that’s hardly the sole preserve of amateur. In fact there’s a very strong Workshop Theatre approach, which also involves the audience and removes the pressure on them to be judgemental like in most of theatre. If you know what you’re doing, and, like you said, you’ve got a script – well, if 11 very sparsely typed pages count as a script – you know where the spaces are, you’re both comfortable with each other, there’s a predictably unpredictable slot for the director and for the audience as well, you both know that you can launch off and do the play – and complete it, which is really important to the process. That’s actually quite a ‘professional’ thing which isn’t such an alien way of creation. Back to the music, it’s like the guitarists – Robert Fripp, for example, who seemed to wake up one morning and changed his guitar tuning to a totally different scale, because he saw it as the only way to get him out of the creative rut, to prevent him from making safe decisions. You’ve already got all that on your bill, except that there’s not that many performers who would want to put their entire careers on the line by doing it, [all laugh] but…

Nathan: I think we’ve never had a career.

Phil: I think it’s because it’s a hobby. I know Nathan has more of a desire to make it like—

Nick: His aspiration?

Phil: —his aspiration—

Nathan: —yeah right—

Phil: —but to me, I know that if you want to do something that is a bit more different, you can’t rely on it. You need to have your own life, another way of making a living, and then this is your hobby, which you take reasonably seriously, try and do it at least once a month. Like Lottie [Bowater] very kindly gives us these slots [at Depresstival Presents…] and we keep the Fringe timetable as a framework to create a new show and all that.

Nick: Quite seriously, this is stuff the Arts Council should be looking out for grantwise.

Phil: I wouldn’t blame them.

Nathan: We’re doing something quite… We still don’t know what we’re doing tonight, for example, but after sitting here talking about our, you know, art and everything, we know that tonight it’s going to be absolute dogshit. But then I think I said something yesterday—

Phil: —it’s back to square one, that’s the thing.

Nathan: Yeah, I said that you have to remember that for eight months of the year or something, Consignia are completely shit and we don’t know what we’re doing and we don’t prepare. You’ve seen a lot of our Lottie gigs and a lot of them, they’re just awful, terrible—

Phil: —but then—

Nathan: —but then eventually—

Phil: —creative work needs stress—

Nathan: —but then eventually, there’ll be like a little thing and that will sort of grow. And also a lot of these gigs are quite good because you hardly ever get laughs, and then when you get a tiny laugh, you’re like, well that, there must be something—

Phil: —essential, yeah—

Nathan: —in there.

Phil: I think it is a collaborative process. That’s the thing as well. It’s not just standup is it? I think that’s where it has theatre dynamics too, where it’s working as a collective basically to make something. That’s why we bring different people in as well to get different views. And then we’ve got friends who we ask to gives us their notes and stuff like that. [Angel Comedy director] Dec Munro gave us a good solid ten minutes of professional notes that we then used at the Fringe. So we take it seriously. But I guess we don’t put any money like into it really. It’s very lo-fi.

Nathan: I find it very much like, what’s that thing of starting off with having no end game? It’s that freedom if you don’t, if you think, if you just put it out there, it’s like if people like it they like it. If people don’t like it that’s fine. That’s actually so freeing because you know, you can pursue these avenues which you probably wouldn’t pursue otherwise but it seems to be getting results. But I dunno if I’m… like hopefully that’ll inform my standup a bit more, hopefully I’ll try and be a bit weirder, but I also think it’s that safety or safety in numbers as well. Cause if there’s two people on stage failing, that makes it a lot easier than just one person on stage descending into failure.

Phil: And I also feel like next year’s show Lemondale will be different to this one, right? I don’t feel, although we might open up these sort of certain pathways and we might be, like you say, anti-theatre, anti-comedy blah blah blah, I think our next year’s show will be a standalone to Panopticon because that’s what makes it interesting. There’s no point in a way, I mean, I don’t know where we’d go if we followed the route started with Panopticon next really. It would be a show that… I can’t see it. I’d rather get more of an idea of… the next year’s show is going to be more at the moment about the rise and fall of an architect but it will be a comedy show. But I dunno—

Nathan: [laughs]

Phil: —I can’t see it. I think it would be different. It’d be quite different to Panopticon. I think it’d be more funny actually.

Nathan: [continues to laugh]

Phil: That’s the thinking.

Nathan: The thing we find with Consignia is not really knowing where it’s going to go.

Nick: I think we’ve sort of got that, somehow… And I think that’s it. And that’s 49 minutes and 20 seconds. A varied 50-minute slot brought to a conclusion soundbite-wise very nicely by Nathan. Exactly as it should be. I think we have a gig to go now…

• Interviewer’s apology: For all the performance studies people in particular, Consignia feature really amazingly lo-budget but interesting audio and video elements in their work, some of which goes on to have another life as standalone pieces. We never got round to talking about that side here, so apologies, but that does provide the perfect excuse for an interview sequel obviously. Maybe soon.

• Link to Roland Crick’s review of The Abridged Dapper 11 Hour Monochrome Dream Show